“Once upon a time, there was a little duck. His name was Egbert. And he lived in Edgewood Park …”

With those words of introduction, I knew it was time for a fantasy flight with one of cousin Esther’s made-up mallard stories. My Juvenile Furniture Company-purchased bed suddenly grew wings as I soared above tall, leafy trees, made friends with frogs and turtles or squealed with delight while sliding across the park’s icy pond – no skates necessary.

At the story’s conclusion, I gave my teddy bear an extra hug and slipped into dreamland.

An escape from reality. Young kids do it all the time.

But as the child of a Holocaust survivor, my realities were … how shall I put it … a bit more graphic. From concealed listening posts – behind a bathtub shower curtain, under a table or in a closet – I unwittingly inhaled the second-hand smoke of my mother’s hush-toned, accented-English descriptions of hell and horror to her new American-born friends.

A hanging here. A sharp-toothed German Shepherd there.

Fantasy. I later realized it empowered my mother to have the will to survive. Imagining a joyous, tearful reunion with her family at the war’s conclusion, she forced herself to endure hunger, illness, beatings, whippings and other degradations. It worked. On her day of liberation by the Red Army in 1945, she was 16 years old and weighed less than 70 pounds.

However, reality intervened. Instead, the tears were for pain and unimaginable loss. Of the 91 family members and relatives my mother could name, six survived. Her sister, Manya – Esther’s mother – was one of them. My mother’s realities became mine as well.

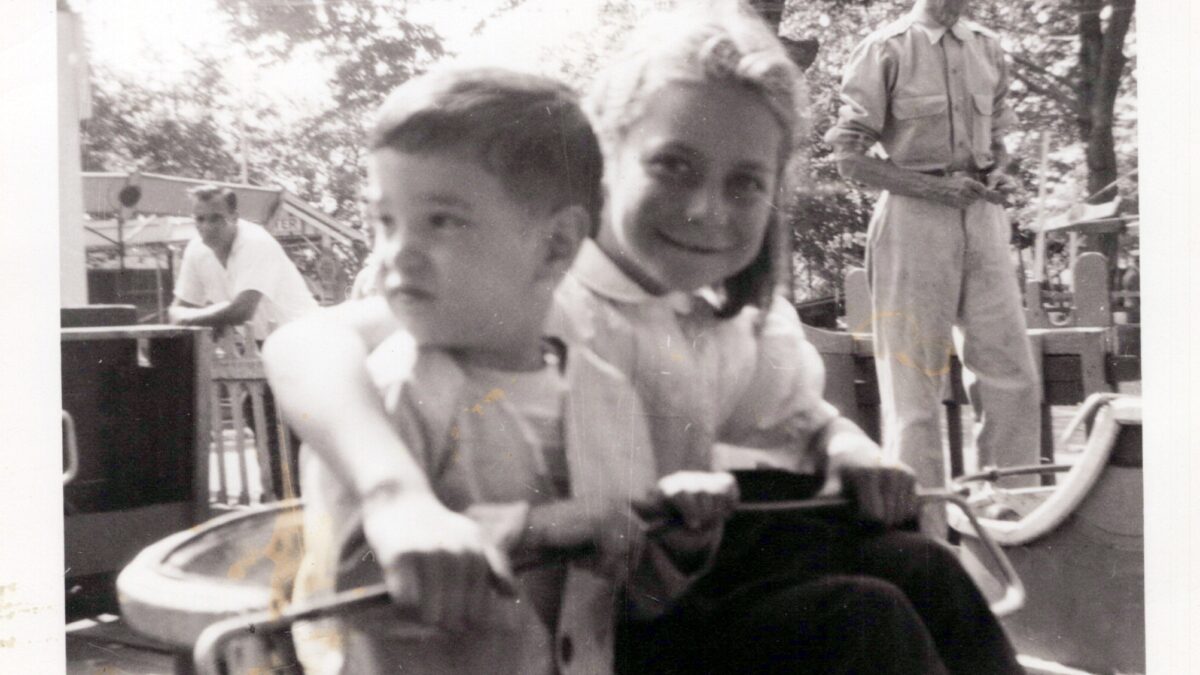

As I grew older, cousin Esther replaced Egbert with Archie, Betty, Veronica and Jughead, pathways for my budding adolescent fantasies (I could do without Big Ethel). These comic book characters were likely part of her own way of processing reality with fantasy.

Following the birth of my children and grandchildren, Egbert re-emerged. His stories – soaring in hot air balloons while orbiting the planets, outsmarting sly foxes, adopting a little brother (appropriately named Quack) – were now mine.

“Once upon a time, there was a little duck. His name was Egbert …”

Through the children’s wide eyes, I saw them painting their own pictures with my words, creating fantasies to help them soar beyond their daily realities. However, with each new Egbert ascension, I also embarked on another chapter in my life-long and perhaps futile journey to escape the frayed but enduring threads of intergenerational Holocaust trauma.

akcpa22@gmail.com Kaplan

Very moving story. Thanks for sharing!

Benjamin

I always loved hearing Egbert’s stories. You should tell us other ones sometimes.

Love,

Ben

Ben

Love you Saba! And Don’t Forget Quack, Egbert’s Brother:)

Love,

Ben

Arthur

My dear grandson, Ben!

You are amazing and – as a little brother myself – I will always remember Quack and assure he has a meaningful voice in my stories.

Love, Saba

Marilyn Teitelbaum

You mean you read Archie comic books too? I would have traded with you !!!!!

Arthur

Don’t forget Richie Rich, the poor little rich boy comic books!